|

REGISTRATION REQUIRED

Expo History

Tales from the Expoverse

Before we look forward to Expo 2025, we're digging back into the weird, wild, and world-changing stories expos have left behind. By Charles Pappas

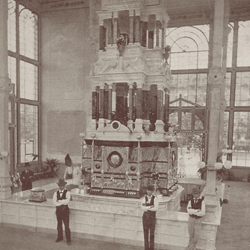

When Queen Victoria visited the Crystal Place on the opening day of the first World's Fair — the Great Exhibition — in 1851, Her Majesty was serenaded by a 600-voice choir that burst forth with Handel's “Hallelujah Chorus” echoing through the Palace, whose length ran a third of a mile. Yet that's a small karaoke night compared to the opening for Expo 2025: more than 10,000 people sang Beethoven's soaring Ninth Symphony to celebrate the start of the six-month event.  One of the most overwhelming encounters you'll have at Expo 2025 is with the 17-meter-tall statue of Gundam, one of the famed robots from Japanese anime. It's huge, but it's not the only giant that's ever loomed over an expo. To symbolize its status as the nation's fourth-largest producer of iron, Alabama forged a 56-foot-tall statue of Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and blacksmithing, for the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Erected within the state's exhibit in the Palace of Mines and Metallurgy, the 60-ton effigy wielded a hammer that weighed 300 pounds. After the expo, the statue was shipped back to Alabama, where the mythical man has since been used for a medley of marketing purposes, with advertisers sticking an ice-cream cone, a Coca-Cola bottle, and even a Heinz pickle in his open hand.  With its 1,200 workers building more than 76,000 cast-iron stoves annually, the Michigan Stove Co. wanted an equally mammoth presence at Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Measuring 25-by-30 feet, a replica of its popular Garland model was built from 15 tons of carved oak painted black and silver to imitate the stoves' nickel-plated veneer. After the expo, the company relocated the stove to its Detroit headquarters, then in 1965 to the Michigan State Fairgrounds. On that location in 2000, the Antique Stove Association fittingly held its annual convention beneath the vast and vintage Garland.  When I saw this statue entwined in front of the French pavilion, I couldn't help but think of Audrey Munson. Wait, who? Known as the Exposition Girl for inspiring a mind boggling 1,500 sculptures at San Francisco's 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE), Audrey Munson was perhaps the world's first supermodel. After posing for premier artists such as Alexander Calder — shown here working on a figure of Munson for the PPIE — Munson eventually faded from public view because of a scandal and lived until 1996. More than a century later, though, her likeness still graces buildings across the United States, from the State Capitol in Wisconsin and the James McMillan Memorial Fountain in Washington, DC, to the Longfellow Memorial in Cambridge, MA.  Many of the pavilions at Expo 2025 look like they belong in a remake of “Blade Runner,” with designs and devices straight out of science fiction. Because science ahead of the curve has always been baked into world expos. Just 19 years after the first oil well was drilled, Augustin Mouchot blazed forth with the world's largest parabolic solar collector at the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Shaped mirrors concentrated the sun's rays onto a black copper container filled with water, which turned the H20 into steam, which then powered a refrigeration unit that produced blocks of ice. Mouchot won the gold medal for his invention, but soon after, solar power was snuffed by the falling prices of coal and oil, along with the expanding system of trains that made the fossil fuels cheap to buy and fast to transport.  The Lithuanian and Latvian pavilions at world expos always punch way above their weight. In Dubai for Expo 2020, Latvia was located next door to the L'Oreal concept store. Inside their moodily lit pavilion, they projected stories on curvy walls and blocks made of peat biomass and birch that seemed like they came from a future where we can program soil to make houses and spin narratives. Lithuania built its elegant pavilion using natural wood, open shutters decorated with traditional folk-art motif, and a clever artificial-fog system that cooled off visitors waiting in line. For Expo 2025 in Osaka, the two countries are exhibiting together in the Baltic pavilion using a design created by the Kettler association. What's really exciting is its wildly innovative interactive installation. Its centerpiece is a leaf-green glass wall that symbolizes both our planet and the dense Baltic forests. Using a unique technology, condensation forms on the glass, turning the wall into a canvas you can draw pictures or write messages on with your fingers — no different than sketching on a steamed-up bathroom mirror or car window with your finger. Tactile, visual, and plainly irresistible, this may turn out to be one of the most popular attractions at Expo 2025.  image: Courtesy of Chicago Historical Society

Food is a huge part of the world expo experience. In Osaka, you'll be able to try everything from Oktoberfest beers to eel pie on top of ice cream. But what's tasting food compared to admiring it like the Mona Lisa?

At the 1893 Chicago World's Fair you could drool over the Prune Knight made entirely of dried French and silver prunes, a globe, eight feet in diameter, covered with 6,280 oranges, and in the Horticultural Building a Liberty Bell made of 4,500 of the oranges. But those most have paled next to French confectioner Henri Maillard French's statue of Christopher Columbus made of solid chocolate, standing 7.5-feet feet tall and weighing in at 1,700 pounds. Next to them Maillard also displayed chocolate reproductions of the “Venus de Milo” and the Roman goddess Minerva, each a svelte 1,500 pounds.  Bandai Namco Holdings is building a “Gundam Pavilion” at the 2025 World Expo in Osaka including a 17-meter-tall statue of a robot. Gundam is the massively popular Japanese military-fiction media franchise in which Gundams (we know them better as 'mecha) are large, bipedal, humanoid vehicles controlled from a cockpit by a human pilot. The company plans to use the Gundam Pavilion to hold a “grand demonstration experiment” in order to “solve the problems of the future society” based on Mobile Suit Gundam (mecha, again), whose tech technology is derived from actual science. Gundam may be the biggest robot ever displayed at an expo, but it's far from the first. Nearly 150 robots wheeled around the grounds at Expo 2020 in Dubai, and Walt Disney flirted with the uncanny valley of humanoid robots with his Audio-Animatronics in General Electric's “Carousel of Progress” at the 1964 New York World's Fair. My personal favorite, though, was Westinghouse Corp.'s Elektro the Moto-Man. At the NY World's Fair of 1939, the seven-foot-tall, 300-pound automaton smoked like the Marlboro Man and blew up balloons. His go-to line was, “My brain is bigger than yours.”  The Cold War heated up at Expo '67 in Montreal after world's fair officials placed the Soviet Union and the United States pavilions across from each other. The Americans stocked their 20-story geodesic dome with Elvis Presley's guitar, Andy Warhol's paintings, and Raggedy Ann dolls, while the Soviets furnished their pavilion with dozens of furs, 6 tons of caviar, and 13,000 bottles of vodka. The Soviet Union's 35-foot-high stylized hammer and sickle served as a stark reminder of tensions between the superpowers that lasted until the “evil empire” crumbled into history 24 years later.  The next time you're asked to produce your photo ID, you can thank (or blame) the 1876 World Expo in Philadelphia. From the very first World's Fair in 1851, Expos experienced problems with accurately identifying exhibitors, employees, press, and various officials who sauntered in and out of their grounds. Issuing them a signed card or pass would have been pointless since it could be handed off to anyone else. That's when the Canadian photographer William Notman, whose Centennial Photographic Co. had the exclusive photographic concession at the 1876 exhibition, came up with an idea for something he called the “photographic ticket.” The photographic ticket was, as you can probably infer from the name, a photo-identification system that was required for all exhibitors and employees at the event. But compared to modern day driver's licenses and other forms of ID, it was a more a work of art than one of bureaucracy. Designed like a book cover, the tickets were engraved by a bank-note company with the touches that made them look like a Willam Morris wallpaper. On the front was the name of the holder, and the position they held at the Expo. Inside, there were rows of numbers representing each day the Expo ran, which could be marked off when the holder entered the fairgrounds. On the right-hand side was the holder's photo, looking way more debonair than any passport picture today.  Commemorating the first permanent English settlement in the United States, the 1907 Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition in Virginia was as much about health as it was history. The “Million-Cup Teapot,” shown here, was part of the national Pure Food movement's exhibit. Located in the organization's 60,000-square-foot Pure Food Building, the colossal but nonfunctioning beverage dispenser helped attract visitors to the building's many other booths. There, staffers for various food manufacturers demonstrated that era's concept of healthy eating, including Quaker Oats oatmeal, Shredded Wheat cereal, Jell-O gelatin, and the most popular food item of all at the event, Snowdrift Hogless Lard.  Back in 1889, many countries — Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Spain, the United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, and Sweden — RSVP'd with a hard pass to their invitation to the Universal Exposition in France that year. Being monarchies, they didn't want to participate in a world's fair celebrating the anniversary of separating royals from their heads. That didn't deter France from constructing a replica of the infamous Bastille prison for the Expo. Once they were inside, visitors were treated to a dank labyrinth of dungeons, instruments of torture, and at designated times, the staged drama of a prisoner's escape from the notorious lockup that was stormed on July 14, 1789.  America's pavilions at World Expos are often received poorly — slagged is probably a more accurate description — over their designs' lack of architectural brio. And then you have the U.S. pavilion at the World's Fair in Vienna in 1873: a giant wigwam. Of course, it was an American wigwam, so the banner and colors of the United States flew at the top in case anyone wondered who was the conqueror and who was the subjugated. Painted on the tent's waxed surfaces were scenes of Indian life. Any attempt at anthropological authenticity on the outside was quickly abandoned inside. There, visitors found a “vulgar buffet” of ale, porter, gin, toddies, and more. Operated by the New York firm Boehm & Wiehl, the bar was a runaway hit, especially the cocktails, such as the Sherry Cobbler, Mint Julep, and Catawba Cobble.  If you use a treadmill, a Peloton, a NordicTrack, or a BowFlex, you can thank a World Expo for your improved cardiovascular system and your washboard abs. When Dr. Gustav Zander was in medical school in Stockholm in the mid-19th century, he began studying the mechanics of muscle building. He found that mechanical devices creating resistance allowed those with injuries to improve with less rigorous stretching than calisthenics and other exercise demand. Zander quickly established the Therapeutic Zander Institute in Stockholm, a state-supported institute using his exercise machines, to help patients with physical impairments improve at a faster pace. But Zander's ideas really took off when he exhibited his exercise machines at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia where they won a gold medal. The idea of mechanized exercise, in an era of rapid industrialization and automated processes — the spinning jenny, the steam engine, the mechanical reaper, the Bessemer Process for making steel — wasn't so far-fetched, so why not apply to the body what we apply to the economy? Zander's post-expo fame helped him become an international fitness entrepreneur, exporting his proto-Crossfit machines around the world. Like a Peloton, they became a status symbol for those who were growing slack from sedentary office work. Unlike the “no pain, no gain” equipment of the current day, though, Zander's contraptions, some powered by steam or electricity, promised you could stand or sit passively while you gained buns of steel.  image: Courtesy of Arthur Chandler

Even before the Eiffel Tower was finished for the 1889 Universal Exposition, it had been subject to the sort of verbal abuse typically only seen on a comedy roasts or on the campaign trail: “giant ungainly skeleton” ... “ridiculous, skinny, factory chimney stack” ... “this truly tragic street lamp” ... “this mast of iron gymnasium apparatus, incomplete, confused and deformed” ... “this hideous column with railings.”

But at least no one accused it of mass murder. Among the 700 suggestions for the centerpiece of the 1889 expo, one was for a tower shaped like a watering can “that would be useful on sultry days,” and a 1,000-foot-tall guillotine, aka the “National Razor” that was used to execute between 15,000 and 17,000 people during the French Revolution's Reign of Terror. While it was obviously never built, it would have been another slap in the face to the monarchies who skipped exhibiting at expo because, by its celebrating the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, it exalted the separation of heads of state from their heads.  “Perfume is a story in odor, sometimes poetry in memory.” — Jean-Claude Ellena But where do you first tell that story so that it becomes a memory? For Lancome founder Armand Petitjean, it was the 1935 World's Fair in Brussels. Inspired by the ruins of the castle Le Château de Lancosme in France (he dropped the “s” to make it easier to pronounce and somehow sound even more French), the former Coty executive debuted five fragrances at the fair, including Tendre Nuit, Bocages, Conquete, Kypre, and Tropiques. Awarded a silver medal, Lancome became one of the many brands given a launch at an Expo even rockets in the space age would envy.  Souvenirs probably go at least as far back as when mammoths still thudded over the earth 4,300 years ago. By the 5th century CE, pilgrims were making their way to Jerusalem to scoop up a bit of the dirt near the Chapel of Ascension where Christ walked before rising to heaven. It was so popular a memento, the Church's caretakers dutifully hauled in fresh soil on a regular basis. World fairs have the have their souvenirs too, naturally. No self-respecting mega-event would be without them. Today for Expo 2025, the must-have expo souvenirs that come to mind might be the Myaku-Myaku (the official mascot of the fair) Tenugui Hand Towel, or ten-gallon hat. Then there's the passport, which you rush through as many pavilions as your legs will carry you, from Azerbaijan to Zaire, to get it stamped near the exit. To the victor — i.e., whoever racks up the most countries' stamps — go the spoils of bragging rights. One of the greatest fairs, the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893, had souvenirs that ranged from the first commemorative stamps ever issued by the U.S. Postal Service to squashed coins, whose crushing cost you perhaps a dime. (Today some of the flattened Indian Head pennies from the fair have gone for as much as $40.) Beyond those, there are two souvenirs I really love. The first was a deck of playing cards whose backs featured Columbus' three ships in pink or blue, and whose faces portrayed scenes and buildings of the fair. These cards were almost ZzzQuil compared to the pop-up books of the fair. Printed in Germany, they came in a set of four books, offering a 3-D fair in miniature of the Expo's best known and most-loved constructions, including Machinery Hall, the Electrical Building, the Naval Exhibit, the Hall of Mines, the Pier, and the Art Palace. Intensely colorful, they recreated the sense of wonder, allowing the reader to look over the buildings as if from the soaring heights of the Ferris Wheel, spinning slowly, gazing down at a glittering El Dorado of dueling electricians Tesla and Edison, of Juicy Fruit and Cracker Jacks, and a miraculous city that inspired Oz.  The Great Exhibition of 1851 was also a decidedly risky business, where many dreaded that open borders would allow foreign influences to topple the host countries' stable, or at least enduring, systems. Even with a feeling of comity in the air, some dreaded foreign manufacturers who, they feared, would spy on — and steal — British production methods. Others trafficked in a more traditional kind of bigotry. In “The World's Fair: Or, the Children's Prize Gift Book,” the author summed up the traits of other nationalities likely to attend or exhibit at the fair: “The Turks do not undress and go to bed at any time, but being seated on a sofa, they smoke till they are sleepy ... A Chinese ... would treat us to strange dainties ... a dish of stewed worms, a rat pie; or perhaps a bird's nest. ... The Spaniards are not either a very active or a very cleanly people.” Still others suspected agents of revolution traveling to England to rouse the rabble. The Times of London fussed that “vagabonds” would make themselves at home in the Expo's surrounding (and upscale) neighborhood. An erstwhile Lord Chancellor declared the Great Exhibition would incite “socialists and men of red colour” to destabilize London. Despite these fears of ideological contagion — the revolutions of 1848, the most extensive wave of revolts in European history, banged and bruised nearly 50 counties — nations eagerly embraced expos as a kind of robust and early Eurovision contest.  Not long after the Eiffel Tower was built for the 1889 World Expo in Paris, a French astronomer writing under the name A. Mercier outlined a cunning plan to cover the Eiffel Tower in mirrors. When the sun set each night, these mirrors could be turned toward Mars and used to send signals to any Martians who lived on the Red Planet. Mercier felt strongly that attracting the attention of extraterrestrials should be humanity's priority. People talked about contacting aliens back then the way people talk about AI now. In 1891, Clara Goguet Guzman, a French widow of considerable wealth, bequeathed100,000 francs to anyone who communicated with any planet within the next 10 years — except for Mars because everybody already knew it was inhabited.  image: Courtesy KADOC-KU Leuven, © Studio Claerhout

Initially best known for its avant-garde, 20-foot-tall, aluminum sculpture, “Risen Christ,” seen here, the Vatican pavilion at Expo '58 is now famous for hiding a remarkable secret.

The building contained a discreet library to which the Russian émigré staffers — one of whom was Leo Tolstoy's grandnephew — steered its 3,000 visitors from the Soviet Union and slipped them the novel “Doctor Zhivago” by the Russian dissident Boris Pasternak. The Central Intelligence Agency had arranged for the subversive work to be secretly printed and covertly distributed at the expo, proving sometimes the pen is indeed mightier than the sword.  World Expos often draw engaged crowds and, occasionally, enraged mobs. At the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Expo, “several thousand men and boys” (women joined the pack too, according to other less sexist sources) attacked the house belonging to promoter Richard Norris, who barricaded himself inside. What could arouse such passions in fairgoers? The controversial baby incubators? The fight between old-time forensics and the newfangled advocates of fingerprinting? Norris had begun advertising that he would stage a bullfight in a 16,000-seat arena at the Expo he had built, naming it after himself and signing superstar Spanish bullfighter Manuel Cervera Prieto, Carleton Bass (known as the American matador), and 35 others to extended contracts. Meanwhile, the St. Louis Humane Society implored Gov. Dockery to “avert this flagrant outrage upon the civilization of the State of Missouri and of the United States.” A number of influential religious organizations joined arms with the Humane Society forcing the governor to acquiesce. One day before the fight, he ordered the St. Louis County prosecuting attorney to arrest all violators since the state already had an anti-bullfighting law. Still, despite the controversy and the governor vetoing the event, Norris sold more than 8,000 tickets at $1 apiece (about $40 today) to the bullfight. When the crowds showed up and realized the bullfight was more of a cock and bull story, they hurled stones, smashed windows, and set fire to the arena. The World's Fair special fire department rushed to the scene but could not prevent the amphitheater from “burning to a black round scar on the ground.” Feeling their job wasn't yet finished, the mob relocated to the promoter's house to further express their displeasure. Rioting and arson weren't the end of it. Three days later, the American matador, Carleton Bass, gunned down the other star matador, Manuel Cervera Prieto, in a dispute related to the cancelled bullfight.  Celebrities could no more resist the call of expos than Odysseus could the Sirens. Thomas Edison and Annie Oakley hurried to them. Henry Ford was an enthusiastic visitor. L. Frank Baum modeled Oz's Emerald City on Chicago's 1893 Columbian Exposition's magical White City. Helen Keller was there too in Chicago and was allowed to “find” a diamond in the Cape of Good Hope exhibit from South Africa. D. W. Griffith, Buffalo Bill Cody, Charlie Chaplin came. Theodore Roosevelt, and John Philip Sousa stopped by Expos. too. But none of the celebrities ever tried what Mark Twain did. The “greatest humorist the United States has produced” explained his desire to become not just an attendee at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Expo but also an attraction. Below is the letter he wrote from Florence, Italy to the president of fair: Dear Gov. Francis: It has been a dear wish of mine to exhibit myself at the great fair and get a prize, but circumstances beyond my control have interfered, and I must remain in Florence. Although I have never taken prizes anywhere else, I used to take them in school in Missouri half a century ago, and I ought to be able to repeat now if I could have a chance. I used to get the medal for good spelling every week, and I could have had the medal for good conduct if there hadn't been so much corruption in Missouri in those days; still, I got it several times by trading medals and giving boot. I am willing to give boot now if — However, those days are forever gone by, in Missouri, and perhaps it is better so. Nothing ever stays the way it was in this changeable world. Although I cannot be at the fair, I am going to be represented there, anyway, by a portrait by Prof. Gelli. You will find it excellent. Good judges say it is better than the original. They say it has all the merits of the original and keeps still besides. It sounds like flattery, but it is just true. I suppose you will get a prize because you have created the most prodigious and, in all ways, the most wonderful fair the planet has even seen. Well, you have indeed earned it. MARK TWAIN.  At the 1867 Paris Exposition, attendees mobbed the Steinway & Sons exhibit in a scene depicted here after the piano maker became the first American manufacturer to receive the Grand Gold Medal of Honor at the fair, standing out from what official accounts said were 158 manufacturers exhibiting 338 pianos. The company leveraged its expo exposure with a program named Steinway Artists, whose ranks eventually came to include Franz Liszt, Vladimir Horowitz, Cole Porter, and others who, though uncompensated by the company, played solely on Steinway pianos. Now 171 years old, Steinway & Sons has built more than 600,000 of the pianos often called “the instrument of the immortals.”  image: Courtesy of A.P. Anderson

To promote his Puffed Rice cereal at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Alexander Anderson installed eight 20-inch-long bronze cannons in his booth. Anderson stuffed the cannons with 6 pounds of raw rice each, capped their openings, and heated them in an oven until the temperature hit 600 degrees. Then, he pulled the cannons out and removed the muzzles, allowing the cylinders to loudly expel the now-puffed rice. The thunderous demonstrations helped sell 250,000 packages of Puffed Rice at a nickel apiece and inspired the company's legendary slogan “Food Shot From Guns.”

image: Courtesy of University of Illinois at Chicago Library Special Collections

Studebaker Corp. went big for Chicago's Century of Progress Exposition in 1933. The car manufacturer added to the tradition of supersized teapots, typewriters, stoves, and other such gargantuan props at trade shows and world's fairs by building the largest model of an automobile ever constructed. Its body made of plaster and wood, the massive — if mock — motorcar measured 80 feet long, and 39 feet high. Beneath its running board was the entrance to an 80-seat movie theater where guests watched films promoting the products Studebaker said were “built like battleships.”

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

TOPICS Measurement & Budgeting Planning & Execution Marketing & Promotion Events & Venues Personal & Career Exhibits & Experiences International Exhibiting Resources for Rookies Research & Resources |

MAGAZINE Subscribe Today! Renew Subscription Update Address Digital Downloads Newsletters Advertise |

FIND IT Exhibit Producers Products & Services All Companies Get Listed |

EXHIBITORLIVE Sessions Exhibit Hall Exhibit at the Show Registration |

ETRAK Sessions Certification F.A.Q. Registration |

CERTIFICATION The Program Steps to Certification Faculty and Staff Enroll in CTSM Submit Quiz Answers My CTSM |

AWARDS Exhibit Design Awards Portable/Modular Awards Corporate Event Awards Centers of Excellence |

NEWS Associations/Press Awards Company News International New Products People Shows & Events Venues & Destinations EXHIBITOR News |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||